Origins

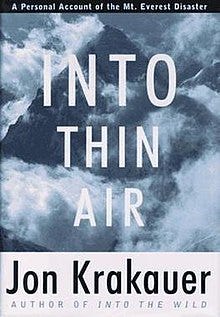

When I was 15, I read Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer, the harrowing yet riveting account of the 1996 Everest Disaster. You’d think that a book about an infamous mountain disaster, detailing the excruciating last moments of 8 climbers lives along with his own near-death experience would make a sane person fear the mountains. But as I finished that book, the opposite seemed to happen to me. I felt their pull, their Call (seriously, listen to that song and tell me you don’t feel inspired). I wanted these types of experiences. Well, not that whole death part - but all the rest. I was intrigued, captivated, entranced, maybe even obsessed. I absorbed other mountaineering books, from Maurice Herzog’s experience on Annapurna, to Ed Viesturs account of climbing K2, to the classic Andean disaster Touching the Void. And soon enough I would not be content just reading about the mountains, I had to experience them myself.

Growing up in Maryland doesn’t exactly lend itself to the mountaineer lifestyle. I wanted big, tall, pointy, glaciated, remote, beautiful peaks. And as I got older, I formulated a plan to get there. First, I would climb an easy mountain in Washington’s Cascade Range, then Mount Rainer, then a tall volcano in Mexico, then Denali, then head to the Himalaya to tackle an 8,000m peak. One mountain a year until I was an expert. Obviously, a flawless plan.

In 2018, I executed the first part of my grand plan. Some similarly entranced friends and I climbed a 10,786ft mountain in northern Washington called Mount Baker. The guided climb involved basic lessons on glacier travel, cold weather camping, self-arresting during a fall, how to pee in a tent, etc. Even though I was miserable most of the time due to my 75L REI backpack digging into my shoulders and the knowledge of my incorrectly bagged poop likely contaminating my gear at the bottom of my pack, it was awesome and threw gasoline on a kindling flame.

When I graduated college in May 2020, I got a job doing engineering at Northrop Grumman outside Baltimore, MD. I was torn. On one hand, it would be a good paying job and I’d be living with my friends in Baltimore. But on the other hand, I knew I was putting off my mountain dreams longer. Trips once or twice a year, the cadence of the past 3 years now, just wasn’t going to cut it if I wanted to become the mountaineer I dreamed of becoming. All of my idols lived near the mountains. I told myself “it’ll just be a few years and I’ll move out west” and “it won’t be long.” I painfully moved the dream to the back of my mind.

But just one month before I was to start in August 2020, I got a call that changed the trajectory of my life. The Baltimore job was no more. I was told to move to Salt Lake City, Utah. At first, I was surprised and, honestly, a bit annoyed that I was suddenly supposed to change all my plans and move out to a place I had never been to, hardly knew anything about, and knew no one. But at this point, I had no other option - so I moved to Utah.

As I explained in my other blog post, being able to experience the mountains daily was life altering and fulfilling. Finally, the flame had room to grow and endless fodder to feed on.

It’s been almost 4 years now since that fateful call and, while I am still no mountain expert, I’ve spent more time in the mountains than I ever could have imagined. And I’m fortunate that I get to finally sit down and address this question: why am I doing this? Why do I choose to spend all weekend climbing up and down mountains, spending thousands of dollars to travel to different ranges throughout the world, occasionally risking mine and others lives in the process? It’s a tough question to answer because, on one hand, I feel the need to justify, ex post facto, why I’ve spent all this time doing a rather silly activity and on the other hand I want to make sure the reasons I give are truly one’s I believe in. But introspection is always that way. Difficult to discern but rewarding when you get it right.

The most famous, yet banal in my opinion, answer to this question is the one the famous mountaineer George Mallory, debatably the first man to summit Mount Everest, gave in 1923: “Because it’s there.” While I often give a similarly vague answer (“because I think it’s fun”), I’m going to try to go a little bit deeper with the following 6 reasons.

Reason 1: Adventure, Exploration and Curiosity

The first, and arguably top, reason for me is to personally experience adventure. “Personally” because today there are so many ways to “experience” these same things through the eyes of others. From YouTube to movies to magazines to books to Instagram. There’s no shortage of adventure to be “experienced.”

But this, to me, seems like a facade. Real experience in life comes when it happens to you. And while I certainly don’t wish to experience all of life’s potential “adventures,” mountain adventure is something I don’t want to live through someone else’s eyes. I want to feel that cold gust of air on my skin, smell that fresh mountain air, see that beauty with my own eyes. To me, these are the experiences that make up life. To not live them is to not fully live. In my opinion, there are only a few of these kinds of things in life that I’ve always believed are essential life experiences. These include things like getting married, having children, having close friends. To me, these things are what give substance to life. The mountains are a gift bestowed upon us. To ignore that gift is to ignore what it means to be human.

There is something different about adventuring in the mountains versus other sorts of exploration. Being in the mountains requires skills which we don’t encounter in everyday life but align with our primitive selves. A cocktail of endurance, evaluating risk, reading mountain conditions, route finding, problem solving, and especially suffering. The merger of these traits superimposed on an immaculate landscape is what seems to connect me to my ancestors and makes me feel alive.

Of course, there are limits to what mountain adventures I want to experience. I never wish to experience what it feels like to free solo El Capitan like Alex Honnold. Or ski Mount Everest like Jimmy Chin. These pursuits seem to lean closer to the adrenaline side of mountain exploration than adventuring for adventures sake. There is a thin tightrope to walk, balancing risk and reward. Do I believe my skills and the quality of the experience justify the potential objective hazards? It’s a difficult question to answer and is one I still grapple with, but its reality in my life assures me that I’m on the right path.

There’s another primal human urge that being in the mountains fulfills: curiosity. By nature, humans are curious creatures and yearn for new experiences. Likely an evolutionary mechanism that benefited our species by exposing us to new, potentially better places/ideas, sheer curiosity has led to some of greatest discoveries…and most brutal demises. To me, the mountains offer an endless buffet of food to satiate one’s curiosity in a world that feels largely discovered, settled and repetitive. I never seem to tire of exploring the mountains, finding new routes or new speeds or new sports to get to a place I may have been a thousand times. Even my home range of the Wasatch, of which I have explored so much, still excites me because I know there is still so much left to discover (climbing routes, ski routes, running linkups, etc.).

One more point about adventure and curiosity. What is something you associate with those two words? For me, it’s children. Every experience for a child is exhilarating because they view it as a new adventure, momentarily satiating their feverous curiosity. But as we get older and those experiences that once excited us as a child dull, I think it’s important that we have something in our lives that gives us that childlike sense of adventure. That feeling of discovery that most of us lost with the years. The mountains do that for me.

Reason 2: Beauty

A huge, and obvious, reason I go into the mountains is because they’re undeniably beautiful. I mean, take a look at some of these pictures from experiences I’ve had in just the past 6 months.

There’s an age-old debate about beauty and art: is it subjective or objective? Is it really only in the eye of the beholder? With the mountains, it seems hard to claim that they’re only subjectively beautiful. There’s something about them - perhaps their mystique, or uniqueness, or imposing nature - that illicits an emotion in all of us, which makes me think there’s something objectively beautiful about them.

Regardless, it feels good to be immersed in beauty. To feel like you’re a part of beauty (finally!). To experience those fleeting moments that perhaps no one else saw or will ever see. To be humbled by the immensity of a range. Or remember how small your problems are in the face of an imposing glacier. There’s something really special in those moments, moments which I’m always chasing because they don’t always happen. Sometimes you’re freezing your ass off trying to get down the mountain as fast as you can, or getting chased by lightning, or drenched in pouring rain. But sometimes you’re riding the sunset, running on a beautiful single-track trail surrounded by red, orange and yellow leaves with the brisk air filling your lungs as you float on forward. That beauty makes it worth it.

Reason 3: Ego

I have a confession to make. No, I don’t love the mountains just because I love the mountains. I also love the mountains because I know that other people do too, and I happen to seek a non-zero amount of external approval. I wish it weren’t true and I wish I could say I do it all for myself, but I’d be lying if I said that. The fact that I know that other people see the mountains I’ve climbed, the routes that I’ve accomplished, the races that I’ve run, gives me a certain satisfaction. It feels good to have an ability that some find impressive and hard, even if others find it futile and silly. It’s self-validating to see other people care and acknowledge the thing you give so much time and effort to. Like the artist who takes his painting to an art show, the actor who accepts an award for his performance, or the writer who puts his ideas out into the world, we each seem to crave some sort of approval from others or at least crave the knowledge that others have viewed our work. Why else would we post on Strava or Instagram or, um, Substack if at least part of us didn’t want others approval? This is why people like Marc Andre Leclerc, a man who blatantly refused to advertise his achievements to the world, are so admirable…for they somehow circumvented this basic human need.

Sometimes I feel like the community I’m in fuels this need. There are so many incredible athletes and mountaineers in the Salt Lake orbit who, as it so happens, tend to be rather savvy with social media. I’m exposed to dozens of people who casually go out for 10+ hour mountain adventures, pushing the boundaries of what I thought possible, such that my bar of what’s “cool” inevitably raises. In a lot of ways I’m happy this dynamic exists because it’s allowed me to do certain things I never thought I’d be able to. But in another way, I feel an invisible pressure to “live up” to the way I think I’m viewed in this community and if I don’t then in some way I “let down” this view. It’s a weird feeling because I don’t feel like I let anyone in particular down, but instead an image of myself that I’ve “built” in both my mind and others. And if I let this image crumble, I’ll have an identity crisis (don’t need that!). So instead, a cyclical relationship is formed: mountainous adventures feed the image, the image feeds my identity, and my identity feeds the mountain adventures.

If you abstract this concept beyond the mountains, you can easily see how this can apply to many other creative outlets. Perhaps to a musician or artist or engineer who feels he has to uphold his perceived image because it forms the basis of his perceived identity. It’s a powerful motivator, but one that can dangerously couple with the inherent risk of being in the mountains. It’s something that I know I have to keep in check.

Eventually I hope to move beyond this reason and be a little more like Marc Andre Leclerc. Maybe being totally confident in your own image and identity is something that comes with age or experience or wisdom. I hope so. But until that point, this will stay a non-zero contributor.

Reason 4: Sense of Accomplishment

Being in the mountains is one of the most straightforward ways, in my mind, to feel a sense of accomplishment. It’s something I can do every day and the only way to achieve it is to struggle. While the sense of accomplishment scales with size and complexity, the small dopamine hit that I receive when summiting a hill or completing a loop still registers with me.

Personal accomplishment help me keep my mental sanity. Too long without a “win” in my book and I begin to fade into despair. Thoughts of inadequacy, complacency, unimportance. It’s a huge motivator behind why I write this blog and create YouTube videos. Striving to accomplish a goal keeps me going and seeing tangible progress towards those goals gives me a sense of purpose.

It is not just the completion of the task that is fulfilling, but the fact that I had to suffer to achieve it. Most people I meet seem to hate suffering, avoiding it at all costs. Society advertise pleasure and leasure because we know that’s what people want. But like so many other things in life, what we want is often not what’s best for us. I love the thought of suffering in the mountains because I know all the most worthwhile things in life come through suffering. What value is there in unearned success? And if this is true, then I am eternally grateful that I chose my own suffering when it could have easily chosen me!

Reason 5: Community

The community of people who have similar mountain ambitions is deep and varied…and I love it. People from all different backgrounds, socioeconomic status, belief systems, Gu preferences, etc. The people I've gotten to meet truly humbles me.

Because of this, I’ve had the opportunity to make some really great friends. There’s something about spending multiple hours with someone in the mountains, on and off the trail, scrambling up rocks with no distractions other than the views/your burning legs, that gives you the opportunity to really get to know someone and form a bond. I’ve had some of best conversations with friends in the mountains, something that I feel a lot of people lack in our otherwise distraction driven world. Having the simple, shared goal of completing a route provides the perfect backdrop to form relationships. Just enough to stay stimulating to our entertainment addicted minds, but not enough to distract from being able to form real conversation. Plus, the fact that it mostly requires your undivided attention removes the phone from the conversation (literally and figuratively). I’ve had some of my most special moments with other people in the mountains and I cherish those memories.

I read a lot about our lack of “third places” in America. A place outside home or work where people can hang out. With the decline in organized religion and the rise of individualistic activities (streaming services, social media, etc.), many seem to struggle to meet people and form meaningful relationships. The mountains have become a sort of “third place” for me, providing a place to spend my free time with other people, with the only price of admission being fitness…and thankfully, no hangover.

Reason 6: A Place to Escape

The last reason I want to cover is a tough but important one. Ever since a traumatic breakup with my college girlfriend in 2021, I’ve struggled with relationships and self-confidence. From “situationships” to rejection to trouble getting matches on dating apps, it’s hard to stay positive with such poor results on something I’ve deemed so important (i.e. see essential life experiences in Reason 1). And when I see friends having success seemingly doing the same things that I’m doing, I can’t help but ask myself “What’s wrong with me?” “What makes me so different?” “Maybe I don’t deserve it?” It can be difficult to stay hopeful.

And to make matters worse, my brain often tries to rationalize these questions by formulating possible reasons why things haven’t worked out. Often these reasons are, well, rather self-deprecating and clearly not helpful. Countering them with a logical response is simply the wrong tool.

Instead, I’ve found that being in the mountains allows me to feel these emotions instead of thinking them. In fact, when I’m alone in the mountains most of my time is spent dealing with emotions and trying to understand why I’m feeling certain things - letting things boil up and simmer as I travel along. Why am I feeling anxious? Or inadequate? Or regretful? Or sad? When I’m in the mountains, I’m simply too tired to rationalize these emotions, which gives me the power to simply feel them deeply. I’ve had some of my most emotional moments in the mountains (often aided by listening to the right song at the right time). Tears of joy running on beautiful ridge lines with towering, glaciated peaks in the background. Tears of gratefulness listening to Flowers on the Grave while running in the Salt Lake foothills on a crisp, cool fall evening. Tears of sadness stuck in a gloomy dark forest alone on the other side of the world. All of these deeply cathartic emotional experiences would have been otherwise impossible. And I’m forever grateful to the mountains for giving me the opportunity to feel deeply when I otherwise struggle to do so.

Great article! I love the mountains too. It’s really pretty

Thank you for letting me into your head. 💗💗💗